In designing an intelligence assessment, I may want to know the level of difficulty that someone is capable of solving. In this case, I would probably look at whether a person is able to solve a particularly difficult puzzle or not. This would be considered a power test. In this context power refers to how well a measurement can differentiate results.

A question that everyone can solve has low power because it doesn’t tell us anything about how people differ. A question that some people can solve and others can’t solve allows us to make finer distinctions between people and therefore would have higher power.

Designing tests isn’t just about the questions but also includes other factors like time. Questions with low power may still be useful if you want to see how quickly someone can solve a number of simple puzzles. You could measure how many puzzles a person is able to solve in some set amount of time. This would be considered a speed test rather than a power test. In this case, it’s ok if you use questions that everyone can solve (low power) because you’re differentiating people based on their speed, not on whether they can answer the question.

Most tests you take in school measure knowledge or skills that you have learned, so they would be considered achievement tests. IQ tests are generally intended to be aptitude tests; tests that predict potential ability. Predicting ability is far more challenging than simply measuring achievement, which is why the design and implementation of intelligence tests can be controversial. While a low score on an achievement test may simply indicate someone hasn’t learned something yet, a low score on an aptitude test could be interpreted as meaning the person is incapable of ever learning something. This interpretation may have major implications for a person’s future, so we have to be particularly cautious when it comes to designing aptitude tests and drawing conclusions from them.

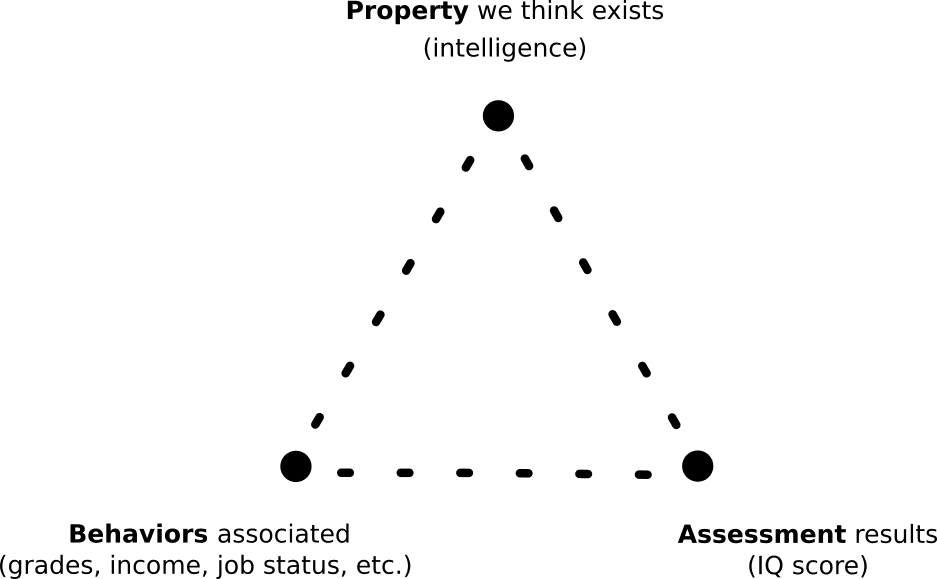

Whenever we consider some hypothetical construct or property like “intelligence” there are three points we should examine closely: The property (which we think exists), the behaviors we associate with this property (the observable behaviors that make us think it exists in the first place), and finally,responses to assessments aimed at measuring this property.

As we consider these three points, we can question the relationships between them. Do those behaviors really represent the property? Does this assessment actually relate to the property? If the answer to both of those questions seems to be yes, then we should find a clear relationship between the assessment and the actual behaviors.

In other words, if grades truly reflect intelligence, and an IQ test is actually assessing intelligence, then we should find a relationship between grades and IQ scores. Ideally this relationship would always hold, but of course, we can imagine exceptions; the brilliant prodigy so bored in class she doesn’t bother doing assignments (high IQ score but low grades) or the charming student whose charisma earns him higher grades than his IQ score might otherwise predict (low IQ score but high grades).

This post is an excerpt from Master Introductory Psychology: Complete Edition