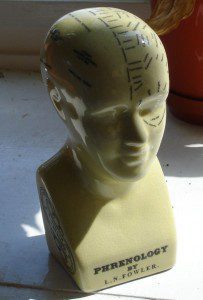

Look in just about any psychology professor’s office and you’re bound to find something like the image above: a model mapping out a person’s “faculties” based on the bumps and dents of the skull. This type of skull study was known as phrenology and was popularized by Franz Josef Gall (1758-1828). Gall and others analyzed thousands of skulls, hoping to find patterns which would link the bumps and dents of the skull to the person’s traits and tendencies for language, love, or lewdness. Despite promise likely spurred by early coincidences, the field was eventually abandoned as researchers realized that they more skulls they studied the weaker the evidence became. You might initially happen to find two or three linguists with similar-enough skull bumps to think that you’re on to something, but keep looking and you’ll likely find other language-lovers lacking these lumps. The truth is that the shape of the skull just isn’t a very good predictor of traits or behaviors.

So if phrenology is so wrong, why does every intro psych book insist on covering it? After all, most textbooks don’t include mention of any number of other false beliefs about the mind from centuries ago. What’s so special about phrenology?

The answer has two parts. First, despite a failed approach, Gall was really on to something when he thought about mapping abilities and traits to regions of the head. What he was really getting at is that it was the brain underneath that controlled such varied things as language ability, personality, or spirituality. He wasn’t looking in the stomach, the gall bladder, or the heart. This seems obvious now, but it really wasn’t so long before phrenology that most people were thinking of personality in terms of the soul, the heart or bodily humors. Phrenology got people thinking about the head as the place where they do their thinking. After a rocky start studying bumps and dents, eventually we got to the fascinating complexity of what was underneath: the brain.

Once we got to the brain, phrenology’s legacy still lingered. Gall’s emphasis on specific abilities being connected to specific regions can be seen as one of the first notions of what we now refer to as localization of brain function: that specific regions of the brain perform specific tasks. Remember that at the time Gall began his cranioscopy there was not yet any solid evidence for localization of brain function. Phineas Gage’s famous accident in 1848 was still decades away and Paul Broca hadn’t yet given his name to a brain area associated with speech.

So while phrenology is now correctly considered to be pseudoscience, we can’t quite consider Gall’s approach entirely wrongheaded.

One Comment on “Why Do We Still Learn about Phrenology?”

Pingback: History & Approaches to Psychology – Resources | Psych Exam Review